The short version of my analysis: MLB sluggers are very good at hitting home runs, and exponentially better than local football and basketball stars.

The longer version of my analysis: I don't feel like going swing-by-swing through all eight derby contestants. However, Chris Davis and Yoenis Cespedes are a fun pair to contrast. Davis is a Paul Bunyan-esque 6'3" and 225 pounds from the left side of the plate, in the midst of a breakout season (after 2012 looked like a breakout season for him). Cespedes is a 5'10", 210-pound chiseled specimen from the right side of the plate struggling in his second season as a pro, though he far from struggled in the home run derby. Davis and Cespedes are both sluggers, but how similar are they? And why would the winner of the derby be the one struggling much, much more during the regular season? I delve into the swings and data searching for answers.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis has a long swing that relies heavily on timing - sort of. More on the timing later. Below are three snapshots taken from the same Davis swing in chronological order:

Notice how the ball is still in the pitcher's hand and Davis's front foot is lifting off of the ground. Many hitters use their front foot as a timing device. Davis's swing begins once his foot lifts off the ground, which in turn means he begins his swing before the ball is even released. Interesting stuff.

On to the next snaphsot...

The ball is roughly 20-25 feet from home plate at this point. Davis's stance has changed considerably since the last snapshot. His front foot is back on the ground about 5 feet in front of where it started. His back knee is now bent, and his hands have drawn back a bit too. The front foot slide has set up Davis's body to transfer all its stored energy into the bat (and ball), while the knee and hand adjustments are a slugger's equivalent of loading a gun. Davis is ready to explode...

...and here he does in snaphsot 3. Davis makes great use of his 6'3" frame. His height gives him leverage, which can be seen in the snapshot above. Davis looks like he is standing tall (and he is), but look at how far apart his feet actually are. He looks upright because he is tall, and more importantly because his front side and arms are quite stiff. Davis's right (front) shoulder is also noticeably higher than his left (trailing) one, creating an uppercut swing path built for lofting baseballs. His hands are also out in front of his body, ensuring all the stored energy that he has lurched forward transfers into his hands, then bat, and ultimately ball.

Chris Davis, even this year, strikes out in over a quarter of his at-bats. He has always struck out a ton, and some of the whiffs are a result of his body and swing. Davis is taller at 6'3", meaning he simply has a larger strike zone to cover. It's easier to throw him strikes, and more strikes generally means more strikeouts. On top of that the uppercut in Davis's stroke gives him a smaller lateral hitting zone. He is trying to hit the ball with the bat at an angle, which means a swing just a tad early or a tad late is more likely to miss. A more level stroke would be more likely to foul off a pitch than miss it altogether, thereby reducing strikeouts a bit. Davis's use of a long stride for a timing mechanism might also harm his contact rate. It's kind of hard to stop 232 pounds of muscle once it starts moving, and Davis puts his strength into motion quite early, arguably before the pitch is even deliver. Davis's timing mechanism, along with his uppercut, are why I say that timing is crucial to his swing.

Sort of. Here's the scary thing about Chris Davis. He has figured out in the last couple years that he is strong enough to muscle pitches out of the ballpark without hitting them perfectly. His evolution as a hitter is apparent in the following spray charts from hittrackeronline.com:

Chris Davis, 2008

Chris Davis, 2009

Chris Davis, 2012

Chris Davis, 2013 (so far)

Davis didn't accumulate much time in 2010 or 2011 in the majors, hence why I don't display his home runs for those seasons. Davis seemed to have a couple general landing spots for his dingers as a rookie in 2008, suggesting maybe a couple general pitches (one inside and one outside, perhaps) that he hit out of the ballpark. Davis trends towards a dead pull hitter in 2009 though, and presumably that trend is why he landed in AAA for the bulk of 2010 and much of 2011. However, with Baltimore, Davis started spraying home runs around the field in 2012 and that trend has continued in 2013. He was also the only derby participant to not exhibit a strong pull tendency in the derby.

Chris Davis, more or less, swings at any pitch in the strike zone, and what's terrifying is that he can hit any pitch in the strike zone out of the ballpark. That's rare, even in Major League Baseball. Furthermore, Davis counteracts the slim hitting zone built into his swing by simply out-muscling the baseball to give himself a reasonable margin for error. The result is a swing that produces loud hits or big whiffs without much between. In other words, Davis has a swing rather perfectly suited for home run derbies. The Richard Sherman celebrities would be wise to study it.

Of course, Davis didn't win the 2013 home run derby. Yoenis Cespedes did.

Yoenis Cespedes

Cespedes, unlike Davis, relies more on pure bat speed and maximizing the strength in his 5'10" frame. Few hitters are more athletic than Cespedes, and he is a better athlete than Davis as we will see in his swing. Below are three snapshots from a Cespedes swing in the home run derby, taken from approximately the same camera angle. I have also tried to time the snapshots so that they are at the same points in each batter's swing:

Cespedes looks much different than Davis as the pitcher releases the ball. His feet are already spread far apart and both are on the ground. Cespedes also starts with his hands higher, above the strike zone instead of at the top of it like Davis has.

This is the money shot right here. What jumps out is how little has changed. The ball is now about 20 feet from home plate and Cespedes hasn't moved his feet. All that's changed is that he has twisted his torso back slightly, actually closing off his front half a bit. He isn't closing himself off though. While Davis pulled his hands back and dropped his back knee to load, Cespedes uses this torso twist to load.

Finally, here is the result. Notice how stiff the front leg is, and how his back knee is almost scraping the ground. Cespedes's weight has clearly transferred to his front side. It's hard to see in this pic, but Cespedes also has his hands out in front of his body. The snapshot below does a much nicer job showing how good of a job Cespedes does getting his hands in position:

Thing of beauty right there. Yoenis's front arm is almost completely straight, meaning he is getting maximum extension. Make no mistake though, the source of Cespedes's power is his core. It's built like a tank, for one thing. You might guess that's where his strength is no matter what sport he is playing. However, his swing is more refined than he likely gets credit for. He can twist his core incredibly fast and keep the bat under control with his strong forearms and wrists. The result is a ferocious swing that produced 32 home runs on Monday night.

Cespedes doesn't do much that he can't stop in his swing until the ball is roughly 20-25 feet from home plate. This is very different from Chris Davis, but Cespedes is not late on pitches because he has terrific bat speed. Scouts prefer "quick" bats like Cespedes's - they generate power without many of the side effects, namely strikeouts. The faster the bat, the more time a batter has to analyze a pitch before swinging, and ultimately the better choices a batter makes about what to swing at and how to swing at it most effectively. Bat speed is largely a product of core strength, or in other words, raw athletic ability. This is why I say Cespedes is a better athlete than Davis. He uses his core more, and with tremendous results.

So why does Cespedes strike out so much and own a measly .221 batting average at the All-Star break?

Some of Yoenis's struggles are likely a bit of bad luck. His BABIP is .252, which doesn't make sense with how fast Cespedes is and how often he hits line drives. Last year Cespedes had a .325 BABIP, which is likely much closer to what would be expected with his talent.

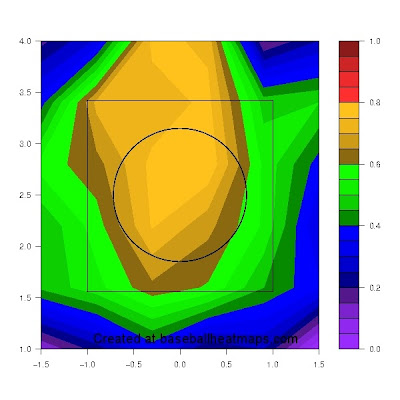

Bad luck is a lazy excuse though. Yoenis is also running a pretty large platoon split between lefties and righties (small sample size though), with righties being the struggle. He is also making more contact on pitches outside the strike zone this year, even though overall he is swinging at fewer balls. Furthermore, Cespedes's value added on fastballs has plummeted this season. So, I decided to go over to baseballheatmaps.com to see if Cespedes was chasing fastballs outside the strike zone. Below is what I found. Colors correspond to how often Cespedes swings at pitches in certain parts of the strike zone:

Cespedes versus left-handed fastballs

Cespedes versus right-handed fastballs

Cespedes chases high fastballs against right-handers. I don't know if that's his biggest problem, but it is a problem that seems easy enough to fix. His swing, based on the home run derby, doesn't look very broken. It's funny how even the most perfect swing can be derailed by bad pitch selection. There is a reason that a .300 batting average, or in other words failing 7 out of 10 times, is a success.

So there you have it, a few more swing analyses to add to the collection, this time with all the bells and whistles that MLB sabermetrics provide. Hooray videos, pictures, and stats!

No comments:

Post a Comment