News of another Mariners trade broke just after the deadline. Happy trails to LHP J.A. Happ. Pittsburgh acquired him by giving the Mariners AAA RHP Adrian Sampson.

Happ has struggled mightily his last few outings, but put a string of solid ones together at the start of the year. He remains, overall, a decent lefty in all likelihood. However, there was a good chance he would get moved to the bullpen and he is a free agent at the end of the season. Happ was another likely player to go today simply because...why not trade him?

Adrian Sampson is a more interesting return than one might expect for a guy like Happ. For one thing, he is a local kid, born in Redmond and drafted out of Bellevue Community College. He is in AAA just two and a half years into his pro career, and while he hasn't posted amazing numbers at any one minor league stop, he has held his own. Sampson gives the Mariners some pitching depth at the end of their staff, either as sixth/seventh starter or long reliever.

There is no word on cash involved in this deal, but I would not be surprised if the Mariners are picking up Happ's remaining salary. Sampson seems a little too good of a get without some cash involved. This is another small, but pleasant, move from the Mariners - unless you go back and remember the M's got Happ for Michael Saunders straight up. But Saunders has been hurt all season, so I guess everybody lost that offseason trade. True to the blue.

Lowe Traded to Jays for Three Prospects

|

| Mark Lowe, from back in the day (Keith Allison, Flickr via Wikimedia Commons) |

Mark Lowe: Enjoying a stunning season, maybe not for the ages, but certainly one of the more heartwarming reclamation projects in recent memory. Lowe was once a hot M's prospect throwing blazing fastballs. His career was derailed by arm problems, and he bounced around for a few years, mostly toiling in the minor leagues. Somehow his velocity returned this season and he emerged out of nowhere to arguably be the M's best reliever. He seems like a legitimately good guy, and the fan in me is sorry to see him go. However, he makes all the sense in the world as a trade target. Lowe's value was never supposed to be this high, and it certainly won't go any higher. Great set-up relievers aren't all the necessary on a non-contender too, especially impending free agents like Lowe.

Nick Wells: 19-year-old lefty in rookie ball, so he's a long-term project. He has a projectable frame at 6'5" and 190 pounds. He was a third-round pick in 2014, which speaks to his prospect status coming out of high school. Wells has struggled early on in his pro career, but we are only talking about 66.2 innings, and the struggles aren't catastrophic.

Jake Brentz: 20-year-old lefty yet to make it out of rookie ball. Significant control issues, though he also has allowed less than a hit an inning and gets almost one strikeout per inning. The stats suggest that Brentz has some decent stuff but he hasn't figured out how to fully harness it yet.

Rob Rasmussen: 26-year-old lefty, and a former

Though we still don't know the third minor-leaguer involved, it appears the Mariners prioritized upside over certainty in this trade. I would expect the third player to be similar to the first two. That's a bit different than other deadline deals within the marketplace, though not necessarily bad.

This is a heck of a return for Lowe, though in line with other deadline deals. The deal probably would have made sense most years even if it was for just Rasmussen or Wells. Acquiring both, plus a wild card like Brentz, is nice. Two thumbs up from me.

Ackley Goes for Flores and Ramirez

.jpg/320px-Dustin_Ackley_at_second_base_(5844771228).jpg) |

| Dustin Ackley (hj_west, Wikimedia Commons) |

Ackley, we know. He was supposed to hit for a high average and the question was how much power he would flash. Instead, he has struggled to hit and gleaned most of his value out of his defense. Ackley is suffering though a miserable 2015 season, easily the worst of his career. Perhaps he will bounce back with a change of scenery, particularly one with a short right field porch like Yankee Stadium.

Interestingly, Ackley was in the announced lineup tonight, so perhaps this trade came together quickly. If Ackley had not been in the lineup would anyone have thought a trade was about to go down? I doubt it, and that says about all you need to know about Ackley's 2015 and why this is not a significant deal.

The Yankees must like Dustin Ackley to some degree, because the Mariners got a respectable return. It is probably a stronger return than what the M's got from the Yankees for Ichiro several years back (D.J. Mitchell and Danny Farquhar).

Ramon Flores is an outfielder with fringy tools. Zduriencik on an interview with 710AM Seattle mentioned that bullpen coach Mike Rojas was on a coaching staff for a team that Flores played with in Venezuela over the winter and spoke highly of his character. Flores got a cup of coffee in the majors this year, and struggled, though only in 32 at-bats. In AAA his triple-slash is .286/.377/.417 which speaks to his scouting reports. I like the high on-base percentage because the Mariners are starved for OBP, though nothing else about the line suggests raw tools or upside. He is probably a fourth or fifth outfielder at best, but brings a skillset the Mariners have largely ignored the past few years. Flores actually takes some pitches, works some counts, and generally maximizes the talent he has.

Jose Ramirez is the more interesting piece in return. Ramirez, although 25 years old, has some upside as a reliable bullpen arm. Zduriencik, in the aforementioned 710AM interview, mentioned that scouting reports have Ramirez pitching in the mid to upper 90s. He has a live arm, and has 56 strikeouts in 49.2 AAA innings this year. Like Flores, Ramirez has some limited MLB experience which hasn't gone well. Control issues have hampered him in a paltry 13 innings over the past two seasons, though the strikeouts have carried into the majors.

The Yankees got the better end of this deal. I still believe Dustin Ackley is a capable MLB player. New York seems likely to put Ackley back at second base, where he was an underrated defender and his fringy offense plays much better. The Yankees just acquired a capable second baseman for spare parts on their 40-man roster.

However, the Mariners got something. They added some outfield and pitching depth, two things they could use. Flores and his on-base skills refresh my soul like a long sip of ice water on a sweltering day. Guys like Ramirez, from time to time, find some command and emerge as quality bullpen arms. Ackley wasn't playing regularly now, he wasn't likely to play regularly in future years, and he had become a disappointment given the lofty expectations that followed him from draft day. The deal is what it is. You can go on with the rest of your day now.

Big Unit Trade, Revisited

|

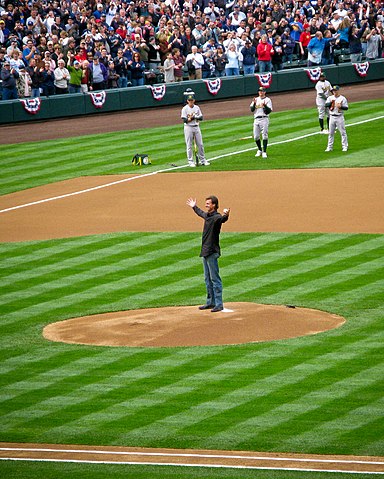

| Randy Johnson, throwing out the first pitch of 2010 M's season (Dave Sizer, Wikimedia Commons) |

In other words, the Big Unit was pretty good. Off the top of my head I would say the title of Best Southpaw Ever boils down to Johnson and Lefty Grove, though I haven't dug into this too deeply. It might be a fun argument to make some day.

Of course, Johnson was a Mariner but (rightfully) went into the Hall of Fame with a Diamondbacks cap on. The Big Unit is also the centerpiece of one of the most significant trade deadline deals the Mariners ever made. He was sent to the Astros in 1998 for Freddy Garcia, Carlos Guillen, and a player to be named later who turned out to be John Halama.

Obviously, this trade was significant at the time. It might be even more interesting to think about now that we know how everything played out, and interesting to revisit with the 2015 trade deadline only days away.

The Astros rented Randy Johnson for three months - and he was amazing for them, amassing a 10-1 record with a 1.28 ERA in 11 starts, with 4 of those 11 starts being complete games. It's hard to argue Johnson could have pitched any better for Houston. They got exactly what they were hoping to get out of the deal.

The 1998 Astros were very good, maybe even great, even though they have largely been forgotten. They ended up going 102-60 in 1998, winning the NL Central. Their expected win-loss based on run differential was 106-56, so they were hardly a fluke. We also now know that the '98 Astros had two Hall of Famers (Johnson and fellow 2015 enshrinee Craig Biggio), plus Jeff Bagwell has a good chance to get in soon too. If he doesn't, he will be a near-miss. This is all to say that this Astros team was loaded, and capable of winning a World Series.

However, Houston lost in the division series to the Padres in four games. The Padres would end up making it to the World Series, where the Yankees curb-stomped them at the peak of their 1990s dynasty. The 1998 Yankees are the only team in my lifetime (so far) that is in the discussion for greatest team ever...and as much as I grit my teeth as a Yankee hater writing it, I have to admit that they were that good. They had what is now known as "the core four" (Jorge Posada, Derek Jeter, Andy Pettitte, Mariano Rivera) all in their prime, plus Bernie Williams, David Wells, David Cone, Paul O'Neill, Tino Martinez, a revived Darryl Strawberry, and a miraculously good Scott Brosius. This was the first of three consecutive World Champions this group would win, and they also won it all in 1996. The core four will be remembered as the heart and soul of this group, as they probably should be, but the supporting cast was deep and really good - likely more than good enough to propel this juggernaut past the forgotten '98 Astros in an alternate World Series universe.

Houston won the NL Central by 13 games over the Cubs, who ended up getting in the playoffs as the wild card winner. It is pretty clear the Astros could have made the playoffs and lost in the first round without Randy Johnson, so on some level he added nothing. He then signed with the Diamondbacks as a free agent after the 1998 season.

Ultimately, Houston gave up three players who all contributed at the MLB level for several years for three months of Randy Johnson that basically was the difference between them being solid NL Central champs and...more solid NL Central champs. I could bust out some fancier analysis, but it doesn't seem necessary. The Astros got the player they wanted but a useless gain, and gave up noteworthy long-term value in the process. I don't see a reasonable argument to be made that this trade worked out for them even with the Big Unit's phenomenal performance.

However, there's a deeper, more interesting question here: Would the Mariners have been better off holding on to Randy Johnson?

Time has softened the toxic relationship that developed between the Mariners and Johnson. He was clearly irked that the Mariners had not given him a contract extension. This predictably spawned trade rumors throughout the season, which included a rather dramatic and public dance with the Dodgers in June of '98, just a few months before he was traded. Initial reactions to the trade were also stunning - not so much because of the fan reaction, which was predictably harsh, but thanks to current Mariners who were shockingly transparent with their frustration.

The Mariners, looking back, were making a very defensible move. Randy Johnson, at the time, was 34 years old. He was a pure power pitcher with incredible stuff - literally some of the most dominant stuff a pitcher has ever possessed in the history of baseball - but also some control problems. He also missed most of 1996 with back troubles. 34-year-old power pitchers with back problems and somewhere between mediocre and above-average control are not the safest bet to age gracefully. Whether performance concerns were the main reasons the M's held off on a contract extension is debatable, but they were good reasons to hold off, especially when you have a phenomenal young shortstop like Alex Rodriguez who was going to eat up a huge chunk of the payroll in the near future.*

*Of course, A-Rod left for obscene money in Texas after the 2000 season, but you'd have to think that by 1998 the Mariners had an eye towards keeping him and what that might take. They also had Ken Griffey Jr. to worry about, and most certainly wanted to keep him at all costs in 1998. Would you have prioritized a 34-year-old Randy Johnson over Ken Griffey Jr. in his prime and an emerging Alex Rodriguez, before any steroid suspicions? I certainly wouldn't have.

Still, for the sake of this argument, let's suppose the Mariners hold on to Randy Johnson, and that they would have been able to sign him to the same deal he got with the Diamondbacks. His initial contract in the 1998 offseason was for four years with an option for a fifth year. He would subsequently sign an extension, but I think that's getting too hypothetical to throw future contract moves in. The first contract gives us something to go with.

Randy Johnson was worth 4.3 bWAR for the Astros in those insane 11 starts I already mentioned. Over the next five years with the Diamondbacks he was worth 39.8 bWAR while also collecting four Cy Young awards (all consecutive, by the way). He was extraordinary, and frankly, much better than anyone could have reasonably expected. He somehow became more dominant and powerful in his late 30s, which is somewhere between unusual and unprecedented.** But that's what he did, so that's what we will give him credit for.

**I take time to point this out because it's easy to be a jaded Mariner fan and say, "well of COURSE Johnson was amazing. That's what former Mariners do and Woody Woodward was an idiot to ditch him when he did." I was among those M's fans with a torch and a pitchfork in the late '90s. In retrospect though, this outcome was historic, and far from guaranteed.

So, the Mariners would have kept about 44.1 bWAR of value if they had held on to Randy Johnson and signed him to a contract extension instead of trading him away. This is an over-simplification that doesn't take into account park effects or the level of competition (particularly the league switch, meaning Johnson faced pitchers instead of DHs), but it gives us some idea of the value the Mariners would have gained with Johnson around.

In that same time frame (August 1998 through the 2003 season), Carlos Guillen was worth 9.1 bWAR, Freddy Garcia 15.6 bWAR, and John Halama 5.2 bWAR.*** That's a total of 29.9 bWAR.

***I was just as surprised as you probably are that Halama was that valuable. He had some clunkers for seasons with the Mariners, but a few bright spots that ultimately provided some forgotten value.

No surprise here in the numbers: Randy Johnson, in five years where he won four Cy Youngs, was more valuable than Guillen, Garcia, and Halama. Still, those three combined produced about 68% of the bWAR that Johnson amassed in that time frame, which suggests they were roughly worth two-thirds of the Big Unit. This is despite Johnson, in my opinion, being much better than what would have been reasonable to predict at the time. Translation: the M's return for Randy Johnson was good, certainly far from the fleecing described in the immediate moments after the deal went down.

Moreover, Johnson cost $64.75 million over the course of the deal while the trio of Guillen, Garcia, and Halama cost only $19.45 million combined through 2003 - less than one third of the Big Unit's price tag. This is especially worth noting given the glut of free agents the Mariners signed in the late 1990s and early 2000s - guys like John Olerud, Bret Boone, Mark McLemore, Aaron Sele, Jeff Nelson, Arthur Rhodes, Kazuhiro Sasaki, and even Ichiro. It's ridiculous to suggest none of these players would have joined the team with Randy Johnson around, but it's equally absurd to suggest all of them would have become Mariners with Johnson's contract on the books. Then again, the Mariners might not have needed all this talent with Randy Johnson - but they also would have had a few more holes to fill, given that they plugged a couple holes by trading Johnson.

The hypothetical can go even farther too: Ken Griffey Jr. was clearly miffed when the Mariners traded Randy Johnson. Does he ask out of Seattle if the Mariners hold on to Johnson? Maybe so, maybe not. The ironic thing is that the M's clearly won the Griffey trade in retrospect, thanks to Griffey's injuries. Not only was Mike Cameron cheaper than Griffey, he was worth more WAR in his four seasons in Seattle than Griffey was for his eight-plus seasons in Cincinnati.

Does A-Rod leave if both Randy Johnson and Ken Griffey Jr. stay? Personally, I think A-Rod still takes the money in Texas, no matter who the Mariners had on their roster. However, Rodriguez was also at least confused by the Johnson trade, if not disappointed and/or angry.

In the end, I am not sure the Mariners would have been better off holding on to Randy Johnson. I am still not sure if they won or lost in the deal, even with almost 20 years of perspective and finished careers to look at.

In my eyes, the trade has become more compelling with time. It is fairly clear that the Johnson deal began the unraveling of the mid-'90s Mariners, but interestingly enough the team the M's wove together in the immediate wake of the Refuse to Lose darlings was at least as successful, if not more successful.

The Mariners have no championships, or even World Series appearances, to show for all the gyrations set off by the Johnson trade, so the next best thing are Hall of Fame players. By that standard, looking back, the Mariners lost out. The Big Unit would obviously go in the hall with a Mariners cap on if he had stayed in Seattle. Still, the odds of the Big Unit going on such an amazing run so late in his career had to be pretty slim, and the odds of the Mariners faring so well in the trade were also slim. The whole sequence of events is quite remarkable.

Peterson's Struggles Point to Organizational Blindspot

Usually minor league baseball articles are rather benign. Imagine all the articles that MLB.com pumps out, those with some info but mostly talking about how great a player or a team is, but then downsize it to minor league baseball. The site is littered with profiles of prospects finding success and working towards the big leagues.

This morning an article about M's top prospect D.J. Peterson popped up on the website, with a common enough title. M's Peterson checks tape, goes yard. The subtitle is just as common: "Generals third basemen socks fifth career grand slam, adds key single." There is no doubt that this article aims to follow the most common MILB.com article archetype - prospect finding success and working towards the big leagues.

The context is important to keep in mind, because I am about to veer away from the main point of the article. While the overall narrative is what would be expected from the title, there are some eye-raising details in the story. The money passage:

This morning an article about M's top prospect D.J. Peterson popped up on the website, with a common enough title. M's Peterson checks tape, goes yard. The subtitle is just as common: "Generals third basemen socks fifth career grand slam, adds key single." There is no doubt that this article aims to follow the most common MILB.com article archetype - prospect finding success and working towards the big leagues.

The context is important to keep in mind, because I am about to veer away from the main point of the article. While the overall narrative is what would be expected from the title, there are some eye-raising details in the story. The money passage:

Seattle has been on the lookout for right-handed power for years, and Peterson made some adjustments to his swing in the offseason in an attempt to improve his chances of getting to the Majors as soon as possible.

The tweaks backfired. Peterson was hitting .211 with a .582 OPS and two homers through the end of May. The 23-year-old wasn't striking out more, but when he hit the ball, the contact lacked the same authority.

"I think maybe in the offseason, I was trying to do a little too much," he said. "I tweaked something and built a bad habit and took a long time to get out of it."

Peterson has attempted to bust out of the slump in the video room. He's studied video of his college days at New Mexico and from earlier in his professional career, noting that his hand positioning and other mechanics were different this season.

The Mariners have a list of high profile busts. Dustin Ackley and Mike Zunino are home-grown players who have struggled more than anticipated. Now D.J. Peterson seems to be going down the same route.

The lazy analysis is that the Mariners do not draft well. However, Jack Zduriencik comes from a strong scouting background. Furthermore, he has drafted some underrated gems, namely Kyle Seager and Brad Miller. Both were respected by national scouts but seen as lesser players than they have become.

My working theory, for several years now, is that the Mariners do not develop players well. This is why I find the Peterson article so interesting. It gives us a glimpse into the development of a Mariners top prospect. The glimpse is concerning.

The article infers that D.J. Peterson made mechanical adjustments on his own in the offseason, without recommendations from the Mariners. That is worth noting. However, it is also clear that Peterson made his adjustments to increase his power output and make the majors faster. Zduriencik droned on last year about how the Mariners desperately needed right-handed power, and Peterson must have listened.

Peterson made his mechanical adjustments as the Mariners signed Nelson Cruz, and well before the awkward trade for Mark Trumbo. He showed up to spring training with the new mechanics, took plenty of batting practice, and no Mariners coach bothered to stop him. All of these moves would reasonable send signals to Peterson that he was doing a good thing. Now, Peterson is going back to tape of his college days to fix his swing.

Let that last point sink in for a second: D.J. Peterson was a better hitter in college than he is after two years in the Mariners minor league system. He has had access to professional coaches for two years and this is the point he is at. The article says Peterson has watched hours of tape on his college swing, so he sounds coachable, to say the least. He has also been the highest-rated prospect on every team he has been on, given that he is rated as the top or second best prospect in the M's system, depending on how much a publication prefers Alex Jackson's upside.* So not only is Peterson coachable, but he should be a player the M's farm system pays very close attention to.

*Alex Jackson, by the way, has also struggled quite a bit in his first year as a professional.

D.J. Peterson, from the sounds of it, tried to turn himself into Mark Trumbo this offseason. It didn't work.

The Mariners have emphasized power at the major league level, especially from the right side of the plate, at an unhealthy rate. They have sacrificed on-base percentage and defense to the point that any gains from the power are more or less lost by the deficiencies. This article about Peterson shows that the mentality has seeped into the minor league system too and you have to wonder what kind of impact it is having.

Consider some more circumstantial evidence:

- Dustin Ackley's walk rate in 2015 is noteworthy because it is the only time it has risen a noticeable amount since he became a Mariner in 2009. That's six years of stagnation or decline in his walk rate. In fact, Ackley has only one MLB season (2012) where his walk total was higher than his highest walk total in college (2008). The difference is small - 59 to 53 - but the real kicker is that it took Ackley 607 at-bats to get those walks in the majors. He had 278 at-bats in his 59 walk season at North Carolina.

- Brad Miller, even as a success story, is a different ballplayer under the M's tutelage. He had marginal power in college and walked about 1.5 times for every time he struck out. Now? He strikes out twice as often as he walks with more power than was projected out of college.

- Kyle Seager, perhaps the best success story of the Zduriencik era, is a different player under the M's tutelage. He came out of North Carolina as a utility player because he had a high walk rate with marginal power at best. He hit 17 home runs his whole career at North Carolina. Ackley, for reference, hit 22 in his final season alone at North Carolina, and Ackley and Seager were at North Carolina the exact same years. Seager's walk rate has sunk as a Mariner while his power has spiked.

- Alex Jackson, the other big M's hitting prospect, has 65 strikeouts to 38 hits this year.

- Tyler O'Neill, in Bakersfield, has 11 walks, 87 strikeouts, and 16 home runs this year. He may hit 30 home runs and only grade out as an average offensive player. He's on pace to do that.

I realize I am cherry-picking here. This isn't the most rigorous analysis. Also, it is common for hitters to walk more and strike out less in college because of the major talent gap between college and the majors and the switch from aluminum to wood bats. Power often sinks too though.

Still, when an MLB team pursues players with a certain skillset, has prospects making adjustments to fit that skillset, and a handful of prospects in the system compile data that suggests they are going for that skillset, it sure seems like there is an organizational focus on that skillset. For the Mariners, this skillset is simple: POWER, at all costs.

Focusing on a skillset is fine. Obsessing over it seems problematic. It has led to obvious holes on the major league roster. A deeper hole might be developing in the minor leagues too. A change in approach probably made Brad Miller and Kyle Seager better players, but an obsession with power at all costs seems likely to hurt more prospects than it helps.

Forgettable First Half Suggests Forgettable Second Half

The Mariners had a tough first half, especially given the expectations going into the year. It is hard to find an interesting spin on this team worth writing about. Seemingly anything noteworthy is depressing and obvious.

The Mariners aren't a comically bad team. They're a sad and bad team. They aren't all that pleasant to watch as they lose, they make bone-headed plays that are frustrating and not even amusing. Even worse, the team has quite a few veterans piling on to the misery, so the sense of hope for the future as the failing unfolds isn't really there.

What follows is my attempt to find something interesting. It's at least something, and without any MLB games today, you could do worse scouring the internet for something to do than the chart and table that follows.

I plotted WAR as a function of WPA on the 2015 Mariners just to see what would happen.

WAR stands for Wins Above Replacement, and is the best sabermetric attempt to date to quantify the value of a player in one number. Think of it as an overall talent rating.

WPA stands for Win Percentage Added. Since so many baseball games have been played in history, it is possible to chart from any game state the percentage of teams that have won in that exact game state. The changes of a team's win percentage can be tracked as game states change, and sliced at the individual batter and pitcher level.

Think of WPA as an overall contribution rating. Obviously, being good at baseball tends to help a player contribute more to wins, but as you might expect, not all situations are created the same. The WPA changes a bunch more with the bases loaded in the 8th inning of a one-run game than when the bases are empty in the 5th inning of a 10-2 drubbing.

Below is a WPA vs. WAR chart for the 2015 Mariners so far. I only included players currently in the M's organization (so no Willie Bloomquist, Wellington Castillo, Dominic Leone, or Yoervis Medina)* because I wanted to see what the current Mariners look like. I also plotted a best fit line, though I don't care much about the line itself. Data points above the line represent players who have higher expected WAR totals than their WPA would "predict." In other words, these players have not been clutch. Data points below the line represent players who have been clutch, or at least accumulated less WAR than their WPA contribution would predict:

*And I didn't catch Rickie Weeks. He should be out of the data set too. Oops. Oh well.

Frankly, I don't see any compelling reasons to expect the second half to look different than the first half. Individual players are likely to rise and sink, but overall the Mariners on paper do not look like a team suffering bad luck. They look like a bad team, and bad teams don't tend to magically get better after three months of bad play.

The Mariners aren't a comically bad team. They're a sad and bad team. They aren't all that pleasant to watch as they lose, they make bone-headed plays that are frustrating and not even amusing. Even worse, the team has quite a few veterans piling on to the misery, so the sense of hope for the future as the failing unfolds isn't really there.

What follows is my attempt to find something interesting. It's at least something, and without any MLB games today, you could do worse scouring the internet for something to do than the chart and table that follows.

I plotted WAR as a function of WPA on the 2015 Mariners just to see what would happen.

WAR stands for Wins Above Replacement, and is the best sabermetric attempt to date to quantify the value of a player in one number. Think of it as an overall talent rating.

WPA stands for Win Percentage Added. Since so many baseball games have been played in history, it is possible to chart from any game state the percentage of teams that have won in that exact game state. The changes of a team's win percentage can be tracked as game states change, and sliced at the individual batter and pitcher level.

Think of WPA as an overall contribution rating. Obviously, being good at baseball tends to help a player contribute more to wins, but as you might expect, not all situations are created the same. The WPA changes a bunch more with the bases loaded in the 8th inning of a one-run game than when the bases are empty in the 5th inning of a 10-2 drubbing.

Below is a WPA vs. WAR chart for the 2015 Mariners so far. I only included players currently in the M's organization (so no Willie Bloomquist, Wellington Castillo, Dominic Leone, or Yoervis Medina)* because I wanted to see what the current Mariners look like. I also plotted a best fit line, though I don't care much about the line itself. Data points above the line represent players who have higher expected WAR totals than their WPA would "predict." In other words, these players have not been clutch. Data points below the line represent players who have been clutch, or at least accumulated less WAR than their WPA contribution would predict:

*And I didn't catch Rickie Weeks. He should be out of the data set too. Oops. Oh well.

Some hot takes on the chart from yours truly:

- What a disaster. The 2015 M's are bunched in quadrant III, the one with both negative WAR and negative WPA. In fact, 13 Mariners fall in this category, and what's even more alarming is that about half of them aren't even close to the origin (0, 0). In other words, the most common 2015 Mariner is below replacement level and has contributed to losses more than wins.

- The Mariners are clutch. There are 13 players above the best-fit line and 21 below it. Remember, above the line represents WAR totals that exceed WPA, below represents WAR totals worse than expected based on WPA. For all the hand-wringing about the M's inability to come through in the clutch, not only could it have been worse, this chart suggests it should have been worse. This really gets back to the first hot take - what a disaster.

- Trade Nelson Cruz now. Cruz has exceeded expectations. Not only is he the M's best hitter, but also their most clutch. His data point on the chart is a legitimate outlier and the safe bet is that his WPA will regress. In other words, Cruz could hit just as well in the second half and see his runs and RBIs dwindle. Cruz had a great first half, batted cleanup for the American League in the All-Star game, and accumulated counting stats beyond what would be expected. If the Mariners are ever going to trade Cruz, they should do it this instant. His value will never, ever be higher as a Mariner. His first half could not have gone any better...which again goes back to the first hot take. What a disaster! The M's hit a prodigious home run with their big free agent splash and are still bad.

- The starting rotation is not clutch, sort of. King Felix, Taijuan Walker, J.A. Happ, Roenis Elias, and Mike Montgomery are all above the best-fit line. This is interesting and might say more about the Mariners offense than any of these starting pitchers. Since the Mariners score so few runs, the runs allowed by starting pitchers will usually carry heavier WPA penalties because they tend to swing outcomes of the game more. A run given up when the score is tied impacts a game much more than a run given up with a couple-run lead, so WPA swings are higher in tight games. For instance if the M's score 1 run, and Elias gives up 2 runs over 7 innings, Elias is going to end up with a negative WPA for the game because that second run especially sunk the chances of winning considerably.

- The bullpen has been deployed inefficiently, sort of. The two data points between J.A. Happ and Kyle Seager represent Carson Smith and Mark Lowe. They have both been amazing, yet both rate as "unclutch." Meanwhile, guys like Fernando Rodney and Danny Farquhar live just above Mike Zunino and rate as "clutch." In reality, bullpen WPAs are a decent place to start a conversation about bullpen use. A manager can control the kind of situation a reliever gets used in much more than any other type of player. So, it is theoretically possible for a manager to load up their best relievers in the highest leverage situations, which would allow good relievers to exceed their expected WPA total. However, both Smith and Lowe have much lower WPA totals than expected. At this point they are pitching the 8th and 9th innings with leads - typically the highest leverage situations - so there isn't much more McClendon can do. Again, this is probably driven more by the M's horrendous offense that can't generate ties or leads to hand over high leverage situations to the bullpen.

If you want to sift through all the data for yourself, here it is as a table sorted from highest to lowest WAR. This is Fangraphs WAR, by the way:

Frankly, I don't see any compelling reasons to expect the second half to look different than the first half. Individual players are likely to rise and sink, but overall the Mariners on paper do not look like a team suffering bad luck. They look like a bad team, and bad teams don't tend to magically get better after three months of bad play.

Jesus Returns

The Mariners made three roster moves last night; of those three, two of the players called up got in the game (Danny Farquhar and Vidal Nuno). However, the player garnering the most attention is Jesus Montero.

Officially the Mariners optioned J.A. Happ to make room for Jesus. In reality, Happ wasn't going to pitch again until after the All-Star break, so really the Mariners are just abusing the schedule to get an extra position player on the roster for this series against the Angels. I fully expect Montero to go back down to Tacoma in the near future.

However, Montero joins a Mariners offense that has sputtered for the vast majority of the year, and he is a AAA all-star slated to participate in the AAA home run derby. Montero also has the "fallen star" status, if you will - a guy everyone thought would hit, then didn't, then had a series of embarrassments last year ranging from reporting to camp way overweight to throwing an ice cream sandwich at a Mariners scout. Now, he's in the best shape of his tenuous Mariners career and slugging away in Tacoma. It's easy to see why Montero feels intriguing. Maybe put better it's easy to see why so many fans want to believe Montero will hit in the majors. It would complete a classic narrative - hot prospect, falls down on his luck, rededicates himself and surges to become what he was always supposed to be. Nothing changes and yet he is transformed from a boy to a man in the process.

That and dingers. Fans might also be happy because Jesus Montero would hit lots of dingers in this scenario.

Since I go to more Rainiers games than Mariners games, I have seen Jesus Montero play quite a bit the last season and a half. Come to think of it, I might have seen him play more than anyone else in the past year and a half. Here are some things you ought to know about Montero 2.0:

.jpg/197px-Jesus_Montero_(7730274866).jpg) |

| Jesus Montero (Wikimedia Commons, Keith Allison) |

However, Montero joins a Mariners offense that has sputtered for the vast majority of the year, and he is a AAA all-star slated to participate in the AAA home run derby. Montero also has the "fallen star" status, if you will - a guy everyone thought would hit, then didn't, then had a series of embarrassments last year ranging from reporting to camp way overweight to throwing an ice cream sandwich at a Mariners scout. Now, he's in the best shape of his tenuous Mariners career and slugging away in Tacoma. It's easy to see why Montero feels intriguing. Maybe put better it's easy to see why so many fans want to believe Montero will hit in the majors. It would complete a classic narrative - hot prospect, falls down on his luck, rededicates himself and surges to become what he was always supposed to be. Nothing changes and yet he is transformed from a boy to a man in the process.

That and dingers. Fans might also be happy because Jesus Montero would hit lots of dingers in this scenario.

Since I go to more Rainiers games than Mariners games, I have seen Jesus Montero play quite a bit the last season and a half. Come to think of it, I might have seen him play more than anyone else in the past year and a half. Here are some things you ought to know about Montero 2.0:

- Don't be fooled by the triples. Montero is still slow. Inexplicably Montero has five triples this year. I saw his only triple at home in Cheney Stadium. It was a rocket out to deep left-center field, where the wall is 425 feet from home plate. I can't say for sure how the other triples have happened, because Cheney's center field is the most unforgiving in the PCL. I would imagine they were hard-hit balls over the outfielder's heads that kicked off walls away from defenders. So, though Montero's footspeed leaves much to be desired, the triples say something about Montero's hitting.

- Montero has a new identity as a hitter. He came to Seattle with a well-earned reputation as a "pure" hitter with plus power because his line drives soared out of the ballpark. In particular, Montero got high marks for his opposite field power. That hitter disappeared in Seattle and was replaced with a fair number of weak groundouts thanks to an obsession for pulling the ball. Montero has played with his batting stance a fair amount, and midway through last season switched to a radically different open stance. It seems to have made a difference. This year, for the first time in his career, he is hitting more fly balls than ground balls, with a ground-out to air-out ratio of 0.77. For his minor league career, that ratio is 1.31, so this is noteworthy switch. Batted ball data like this tends to regress fairly quickly. That big of a gap suggests a different hitting profile. This is a switch which helps Montero take advantage of his best tool (power) while hiding his worst tool (speed). It might be the best reason to believe he will perform better in the majors now than before.

- Montero swings at almost everything. Jesus Montero has struck out in 18% of his plate appearances this year, while walking in a shade under 6% of them. It is very easy to believe these numbers even after watching only a few Montero plate appearances in Tacoma. Pitch location and pitch type data isn't as readily accessible for minor league games, so I can't go much further with this analysis. The strikeout rate is high, but not so high to think that Montero will fail as a hitter in the majors given his power. However, that strikeout rate combined with the walk rate tells a more alarming story. I'm not convinced that MLB pitchers will have to throw Montero strikes to get him to swing. This is the biggest reason to believe Montero will struggle in the majors, and it's a mighty big one.

In the end, this is a medium-length post about almost nothing. I doubt Jesus Montero gets many at-bats before going back down to AAA. I also doubt that he's in a position to contribute any more than current Mariners. He is likely to strikeout a ton with a low average, low on-base percentage, and some home runs thrown in. Montero probably falls somewhere between Mark Trumbo and Mike Zunino as far as what we could expect from him if he played regularly.

I think Montero's promotion has more to do with symbolism and psychology. Montero could be out of baseball right now. Last season was that disastrous and it seemed fairly clear that the Mariners were down to their last straw with him. Montero buckled down and clearly worked hard in the offseason. He is also producing, albeit against AAA pitchers in a way that suggests MLB pitcher might take advantage of him. Still, Montero was slaying AAA pitching with some authority last year before his season completely fell off the rails. This promotion back to the bigs has to feel like a real sign of his hard work paying off. Plus, who knows, maybe Edgar Martinez can convince Montero to work some on his plate discipline, which would go a long ways towards Montero developing into a viable option at first base.

Making Meaning of 0 for 14

In case you had to do something like, say, work from 12:30-4pm, you might have missed a somewhat thrilling Mariners defeat at the hands of the Tigers. Detroit won 5-4 and in the process the two teams tied the Safeco Field record for most home runs in a three game series (14, with a pair of home runs launched in yesterday's matinee and 12 in the first couple games).

On the surface, four runs ain't so bad for this M's offense, or really any offense. It's a pretty average output. However...*in my best 30 for 30 promo voice* What if I told you the Mariners went 0-for-14 with runners in scoring position in a game they lost by one run?

For the record, that's exactly what happened yesterday. Frankly, it's stunning the Mariners found a way to score four runs without ever getting a hit with a runner in scoring position. I don't have data on how rare this is, but it seems like something that's just about impossible to do. Almost as impossible, perhaps, as going 0-for-14 with runners in scoring position.

The M's lack of clutch hits is hardly a new story. Reporters and fans alike bemoan this team's anti-ability to strand baserunners with reckless abandon. The Mariners are now hitting .205 with runners in scoring position for the season, which is dead last in the American League. Numbers like this suggest that the Mariners have a problem hitting with runners in scoring position, and games like yesterday's matinee provide individual examples of what this problem looks like.

However, blaming the M's offensive woes on bad clutch hitting wreaks of confirmation bias to me. Yes, the Mariners hit poorly with runners in scoring position, but they hit poorly in every situation. The Mariners haven't hit well, period. So is it all that surprising that they also struggle to hit with runners in scoring position?

Yesterday's game finally motivated me enough to investigate how badly the Mariners have hit with runners in scoring position, and figure out if they "aren't clutch." Clutchitude, or clutchness, or whatever made-up word you would like to use (I prefer clutchitude, so that's what I'll use), is a topic still debated between more traditional followers of the game and statheads.

Long story short, statistical studies tend to strongly suggest that things like particularly good or bad hitting with runners in scoring position have no predictive power. In other words, good and bad clutch hitting don't continually pop up in player stats year after year like a consistently above or below average on-base percentage pops up for players. Therefore, clutchitude is not a skill. The argument is strong, but debate rages on because it is at odds with our own narratives about the game, and even personal experiences playing the game.

Anyway, I am not interested in predicting if the Mariners will continue to hit poorly with runners in scoring position. I am interested in how badly they have already done, and if their hitting so far is truly un-clutch based on their overall hitting trends. This is not a post about arguing the deeper value of clutchitude. It is a post about figuring out how unlucky the 2015 Mariners have been, because there is no debate that the Mariners are the worst hitting team in the American League with runners in scoring position, and that they just went 0-for-14 in the clutch in a game they lost by a run.

Let's start with some numbers. Below is a table summarizing the Mariners offense overall, and showing specifically their offense with runners in scoring position:

There is really only one thing worth talking about, the BABIP (batting average on balls in play). It is true that a higher percentage of balls hit by the M's with runners in scoring position turn into outs. If their BABIP with RISP (what a great combo of acronyms) was the same as their overall numbers that would also drive up their team batting average, on-base, and slugging. In fact, simply making their BABIP .272 in with runners in scoring position would change their triple slash with RISP to .233/.318/.372, which would make them better in clutch situations given the significantly higher on-base percentage than they exhibit in their overall numbers.

So, how unlucky has the M's BABIP been? The quickest, simplest way to test this is to treat RISP as a random subset of the M's overall numbers. There is a statistical rule of thumb helpful here. We can use 1 over the square root of n, where n in this case is the number of plate appearances that the Mariners have had with runners in scoring position. Then, we take that number and add/subtract it to get a plausible range for what the M's actual ability is in that situation. The concept is simple - the bigger the sample size, the smaller 1 over root n gets, which suggests that the more data we have the more reliable it is.

1 over the square root of 745 works out to 0.0366 (and lots more decimals). So, applying this to BABIP with RISP, we would expect the M's "true" BABIP to be somewhere between .208 and .282. So far it has actually been .272, which falls within this range. Just for fun, here are the rest of the expected ranges based on their stats with RISP:

Every single overall statistic falls within the range suggested by the M's statistics with runners in scoring position when considering the variance that would be expected given a sample of 745 plate appearances. It is interesting that the Mariners hit worse with runners in scoring position, but the takeaway here is that they haven't hit so much worse that it's beyond random noise in the data.

On the surface, four runs ain't so bad for this M's offense, or really any offense. It's a pretty average output. However...*in my best 30 for 30 promo voice* What if I told you the Mariners went 0-for-14 with runners in scoring position in a game they lost by one run?

For the record, that's exactly what happened yesterday. Frankly, it's stunning the Mariners found a way to score four runs without ever getting a hit with a runner in scoring position. I don't have data on how rare this is, but it seems like something that's just about impossible to do. Almost as impossible, perhaps, as going 0-for-14 with runners in scoring position.

The M's lack of clutch hits is hardly a new story. Reporters and fans alike bemoan this team's anti-ability to strand baserunners with reckless abandon. The Mariners are now hitting .205 with runners in scoring position for the season, which is dead last in the American League. Numbers like this suggest that the Mariners have a problem hitting with runners in scoring position, and games like yesterday's matinee provide individual examples of what this problem looks like.

However, blaming the M's offensive woes on bad clutch hitting wreaks of confirmation bias to me. Yes, the Mariners hit poorly with runners in scoring position, but they hit poorly in every situation. The Mariners haven't hit well, period. So is it all that surprising that they also struggle to hit with runners in scoring position?

Yesterday's game finally motivated me enough to investigate how badly the Mariners have hit with runners in scoring position, and figure out if they "aren't clutch." Clutchitude, or clutchness, or whatever made-up word you would like to use (I prefer clutchitude, so that's what I'll use), is a topic still debated between more traditional followers of the game and statheads.

Long story short, statistical studies tend to strongly suggest that things like particularly good or bad hitting with runners in scoring position have no predictive power. In other words, good and bad clutch hitting don't continually pop up in player stats year after year like a consistently above or below average on-base percentage pops up for players. Therefore, clutchitude is not a skill. The argument is strong, but debate rages on because it is at odds with our own narratives about the game, and even personal experiences playing the game.

Anyway, I am not interested in predicting if the Mariners will continue to hit poorly with runners in scoring position. I am interested in how badly they have already done, and if their hitting so far is truly un-clutch based on their overall hitting trends. This is not a post about arguing the deeper value of clutchitude. It is a post about figuring out how unlucky the 2015 Mariners have been, because there is no debate that the Mariners are the worst hitting team in the American League with runners in scoring position, and that they just went 0-for-14 in the clutch in a game they lost by a run.

Let's start with some numbers. Below is a table summarizing the Mariners offense overall, and showing specifically their offense with runners in scoring position:

STATISTIC

|

OVERALL

|

RISP

|

Plate Appearances:

|

3,141

|

745

|

Batting Average:

|

.231

|

.205

|

On-Base Percentage:

|

.293

|

.290

|

Slugging:

|

.378

|

.344

|

BABIP:

|

.272

|

.245

|

Strikeout Rate:

|

21.9%

|

23.2%

|

There is really only one thing worth talking about, the BABIP (batting average on balls in play). It is true that a higher percentage of balls hit by the M's with runners in scoring position turn into outs. If their BABIP with RISP (what a great combo of acronyms) was the same as their overall numbers that would also drive up their team batting average, on-base, and slugging. In fact, simply making their BABIP .272 in with runners in scoring position would change their triple slash with RISP to .233/.318/.372, which would make them better in clutch situations given the significantly higher on-base percentage than they exhibit in their overall numbers.

So, how unlucky has the M's BABIP been? The quickest, simplest way to test this is to treat RISP as a random subset of the M's overall numbers. There is a statistical rule of thumb helpful here. We can use 1 over the square root of n, where n in this case is the number of plate appearances that the Mariners have had with runners in scoring position. Then, we take that number and add/subtract it to get a plausible range for what the M's actual ability is in that situation. The concept is simple - the bigger the sample size, the smaller 1 over root n gets, which suggests that the more data we have the more reliable it is.

1 over the square root of 745 works out to 0.0366 (and lots more decimals). So, applying this to BABIP with RISP, we would expect the M's "true" BABIP to be somewhere between .208 and .282. So far it has actually been .272, which falls within this range. Just for fun, here are the rest of the expected ranges based on their stats with RISP:

- The M's true batting average is somewhere between .168 and .242.

- The M's true on-base percentage is somewhere between .253 and .327.

- The M's true slugging is somewhere between .307 and .381.

- The M's true strikeout rate is somewhere between 19.5% and 26.9%.

Every single overall statistic falls within the range suggested by the M's statistics with runners in scoring position when considering the variance that would be expected given a sample of 745 plate appearances. It is interesting that the Mariners hit worse with runners in scoring position, but the takeaway here is that they haven't hit so much worse that it's beyond random noise in the data.

The Mariners biggest problem with hitting in the clutch is that they are bad at hitting. Their shortcomings are more noticeable in crucial situations, that's all. For instance, the Mariners strikeout almost as often as they get hit, so it is reasonable to expect a strikeout just as much as a hit with the game on the line - and that's even before we account for things opposing pitchers and managers might do. Some starting pitchers save their fastest fastballs and sharpest breaking pitches for tougher situations, and late in games a manager is more likely to call on tougher relievers when the game is on the line (in other words, when runners are in scoring position).

It is plausible that the Mariners have bad luck in the clutch. However, it is much more plausible that the Mariners are simply bad at hitting and that the "tough luck" we've witnessed is a combination of noise in the data and pitchers buckling down in crucial situations. That's what it means to be True To The Blue in 2015.

Taylor Up, Bloomquist Gone

|

| Hey look, that's Jose Vidro in the background! (Wikimedia Commons, authors OlympianX & Andrew Klein) |

Taylor is younger than Bloomquist and also a better player. He brings superior defense at shortstop and likely second base - and maybe even all the other spots Bloomquist plays if he is asked to go wherever just like Willie Ballgame has had to do throughout his career. Taylor also flashes surprising power in the minors for his build and swing type, but by no means is he a power hitter. Still, he probably possesses more power than Bloomquist.

So, basically, Chris Taylor is a better baseball player than Willie Bloomquist in all phases of the game. The most surprising part of this move is how long Bloomquist survived on the roster, given the M's depth of solid middle infield prospects. I don't know why the Mariners pulled the trigger on this move today or what kind of playing time Taylor will receive moving forward, but it is fair to assume that this move is skin deep as far as its motives. The Mariners are a more talented team with Chris Taylor taking Willie Bloomquist's place.

Few players have a career quite like Bloomquist. He is the definition of replacement level. In 3,136 plate appearances he has amassed a grand total of 1.0 WAR. For comparison, that's about what Mike Trout has produced every three weeks or so while in the majors. Bloomquist took about 12 years longer to accumulate the same amount of production.

I never understood why the Mariners signed Willie Bloomquist for two years in the 2013 offseason. Anyone could see the middle infield logjam developing from a mile away, and here we are. They signed him after they had Robinson Cano in the fold, and well before Nick Franklin got traded away. The deal never made any sort of sense, and while it didn't break the budget, it still seemed so unnecessary. In fact, why couldn't the money the M's threw at Bloomquist been used on a legitimate backup catcher?

None of these issues I have with Willie Bloomquist and his contract really have to do with Willie Bloomquist. It's amazing to look at his lengthy career in the majors, devoid of anything approximating a "career year" or anything that gave hope he might have a short stint as a serviceable starter, and wonder just how he hung around for so long. It's not like the Mariners were the only team to irrationally love him. Both the Royals and Diamondbacks employed him too. Maybe one organization could be dumb and make silly mistakes year after year. Three organizations making the same irrational choice is less likely.

I can only find one logical conclusion: Willie Bloomquist is legitimately one of the "good guys" in baseball. He must be fun to have around a clubhouse and the kind of guy that has the respect of his peers. Bloomquist never played much, and when he did he was neither an asset nor too large of a liability, so there is no good reason he should have stuck around the majors so long. He must have brought other things to the table that don't show up in box scores.

For instance, Peter Gammons tweeted out today that Adam Jones credits Bloomquist for much of his success. I find that fascinating. Jones didn't spend much time with Bloomquist as a pro. We barely got to know Adam Jones in Mariner blue before he left in the ill-fated Erik Bedard deal, and yet he was apparently around long enough for Willie Ballgame to do something influential and momentous for him.

So consider this my farewell to Willie Bloomquist. I like Chris Taylor quite a bit and thought he should have been on the ballclub at least a month ago, so I can't say I'm sorry to see Bloomquist go. However, Bloomquist's 72 at-bats this season are also not the reason the Mariners have struggled. They hardly made a dent on the field, in true Bloomquist fashion.